Painting in the Harlem Renaissance

Painting in the Harlem renaissance

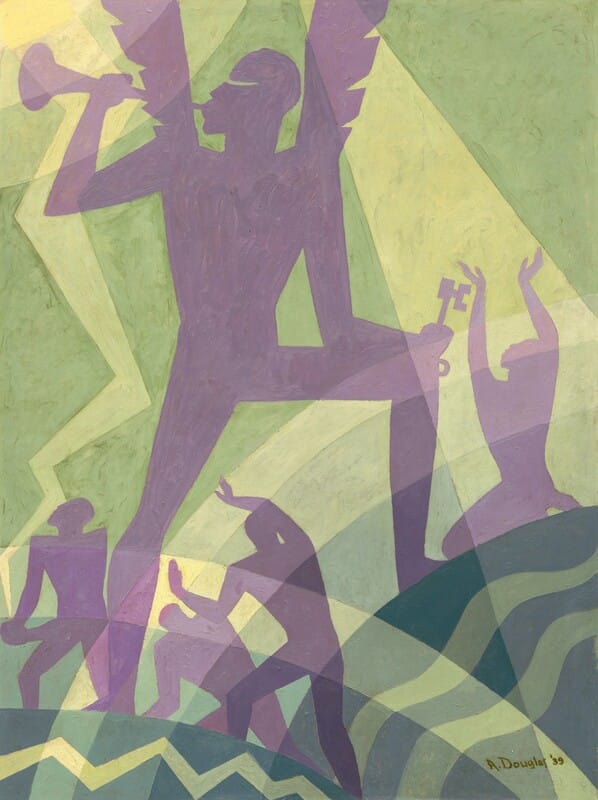

Painting during the Harlem renaissance consisted of different subjects and styles, reflecting experiences of African Americans, history, and culture. Aaron Douglas, born 1899 and often known as the ‘father of African American art’, was one of the most well-known painters from the time (Harlem renaissance, Wikipedia, 2018) but the contribution to art within the Harlem renaissance did not stop at that. Women and the LGBTQ2+ community played a significant part within the Harlem renaissance often being overlooked or ignored up-until recently when the movement was re - evaluated. Individuals like Gladys Bentley and Bessie Smith contributed to music and the performing arts with the blues genre and many of the painters from the time included women; painters like Lois Mailou Jones, Laura Wheeler Waring, Suzanna Ogunjami and Margret Taylor Goss Burroughs paved the way for African American women(Kelly-Christina grant - AWARE, 2024).

Painting during this time focused on community, black identity and history, using modernist and traditional methods to challenge the harmful stereotypes put on the African American community. Aaron Douglas blended both afro -cubist as well as art-deco with added ancient Egyptian motifs to promote a powerful message to those that were oppressed and those who weren’t. Laura Wheeler Waring took a traditional approach; painting what she saw and lived. Louis Mailou Jones similarly used ancient Egyptian motifs to hint at an ancestral history (Isherwood-Lewis, R. 2025).

Louis Mailou jones, born 1905, was one of the most well recognised African American female painters at the time. Her career began in the 1930’s and worked her whole life painting what she saw and experienced. Her style shifted with her travels to places like Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean where she gained in a new eye for painting (Louis Mailou Jones, Wikipedia, 2018). She created well-known pieces, some of which include: ‘Arreau, Hautes - Pyrenees’ inspired by France in 1937- 1945 during her time studying and teaching there, another example being ‘Ode to Kinshasa’ was painted in 1972 when she visited Democratic Republic of Congo in Africa and it’s very evident in the way she used vibrance as well as texture (NMWA, N/A).

Laura Wheeler Waring, born 1887, was another African American artist well known for her landscape and portraits during the Harlem renaissance. Her career really came to light in 1927 when she received a gold award in fine arts given to her by the Harmon foundation (Laura Wheeler Waring, Wikipedia, 2020). She was one of the few African American women to study and exhibit art in France. Some of her well-known works included ‘After Sunday services’, an oil on canvas paintings, made 1940 and ‘Portrait of a boy’, made 1930, just to name a few. Later in her life she taught classes at Cheyney university in Pennsylvania and did so for the next thirty years after returning from Paris (Laura Wheeling Waring, Artnet, 2024).

Aside from the more well-known female artists there was also a woman named Suzanna Ogunjami, a Jamaican-Sierra Leonean painter, active from 1928- 1934 (Suzanna Ogunjami, Wikipedia, 2025). Suzanna Ogunjami was born in Nigeria, moved to Jamaica in her youth to finish her primary schooling and later moved to New York City in 1921. She attended the Teacher's College of Columbia University to study courses in textiles and arts (Ottenberg, S. 2015), later graduating with a bachelor's degree in science in 1928, and a Master of Fine Arts degree in arts education in 1928. Some of her only known pieces include: ‘Full blown magnolia’ an oil painting on burlap, made in 1935 and currently housed in Hampton University Museum Collection in Virginia (USA) as well as ‘A Nupe princess’ an oil on canvas piece made in 1934 and it depicts an older woman who is a royal member of the Nupe kingdom and is currently housed in Fisk University Galleries, Fisk University, Nashville (Philips collection, 2024).

Why is it important to recognise these individuals? What was lifelike for these women?

The idea of remembrance has been implemented as far back as human history's beginnings; craving for a legacy that makes their lives purposeful (Singh, S. 2025). Not much is known about African American women of 1920’s and 30’s due to the intersectionality and the overlapping of racism and sexism; things that made them societally invisible. A lot of these women had to raise children, work, and survive meaning most did not even get the opportunity. (Jenainati, C., Groves, J. and Milton, J. 2019). It did not just stop there as it also effected the lives of these women through systematic disenfranchisement and harmful stereotypes. Systematic disenfranchisement is the restriction of suffrage of a group of people based on opinions or stereotypes; preventing them to vote based on discrimination or prejudice. It conveys intersectionality, where many social and political identities experience discrimination that ultimately overlaps (Wikipedia, Disfranchisement, 2019) (Intersectionality, Wikipedia, 2019).

After the 19th amendment in 1920 African American women were allowed to vote but due to the Jim crow laws in the south particularly it blocked them from exercising it; the Jim crow laws were segregation laws enforced in the south (Jim crow laws, Wikipedia, 2018). Black women specifically have been fighting for freedom for about 400 years beginning with the arrival of slavery, in America, in the 1600s; a fight for freedom and a voice, a gruelling endeavour for these women, women who were often forgotten or ignored. An example being, Suzanna Ogunjami, a Jamaican-Sierra Leonean painter, active from 1928- 1934 (Suzanna ogunjami, Wikipedia, 2025). She was an independent artist that potentially didn’t just use paint but also explore metalwork, printmaking and jewellery; we can’t say for sure. Her work was only shown briefly in exhibitions in New York amongst other places. She later moved to Jamaica and never seen or heard of again. Despite my efforts to source something more than what was already recorded I found nothing: that alone conveys the lack of knowledge or voice of these individuals. She was an important part of the diverse histories within the harem renaissance and yet no one knows who she is.

Audre Lorde puts it best when she writes, "For in order to survive, those of us for whom oppression is as American as apple pie..’, Lorde’s words here say that in order to survive, those who are in a position of oppression, is as common and ‘American’ as apple pie; it’s normalised and accepted. It is a biting comment on how this is continuing and how those oppressed must be constantly on guard and the idea that those have to ‘survive’ and not live. It gives us an insight to the power dynamic; navigating a world in which is already heavily against them. She goes onto re-enforcing her point by saying, ‘have always had to be watchers, to become familiar with the language and manners of the oppressor, even sometimes adopting them for some illusion of protection.’ and it’s reminding those that these things still exist and it’s unforgiving in the way she writes it. The passage itself highlights the pressure and burden on those who are oppressed; one that many were forced to shoulder. (Lorde. A, p. 114, 1984).

The erasure of African American history is a form of oppression itself, but remembrance becomes a way of reclaiming power. By acknowledging figures like Suzanna ogunjami, whose work had been left unseen, and by listening to voices by Audre Lorde, we oppose this ideology imposed by racism and sexism. Remembering these women and hearing these voices is not simply acknowledgment of the past but also showing the struggles of these individuals to shape the future. Their silent survival is a testament to their resilience; transforming invisible to visible and absence into presence. In remembering, we affirm that African American women aren’t forgotten but a large and significant part of the fight for freedom; central to the story of freedom and voice.

References: [IN ORDER]

- Wikipedia Contributors (2018). Harlem Renaissance. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harlem_Renaissance.

- AWARE Women artists / Femmes artistes. (2024). The Trailblazing Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance — AWARE Women artists / Femmes artistes. [online] Available at: https://awarewomenartists.com/en/decouvrir/les-artistes-pionnieres-de-la-harlem-renaissance/.

- Isherwood-Lewis, R. (2025). The Harlem Renaissance, art, politics and ancient Egypt. [online] UCL Faculty of Social & Historical Sciences. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/social-historical-sciences/geography/research/research-centres/ucl-equiano-centre-exploring-black-histories-race-and-anti-racism/educational-resources-fusion-worlds/harlem-renaissance-art-politics-and-ancient-egypt.

- Wikipedia Contributors (2019). Lois Mailou Jones. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lois_Mailou_Jones.

- National Museum of Women in the Arts (n.d.). Loïs Mailou Jones | Artist Profile. [online] NMWA. Available at: https://nmwa.org/art/artists/lois-mailou-jones/.

- Wikipedia. (2020). Laura Wheeler Waring. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laura_Wheeler_Waring.

- Artnet.com. (2024). Laura Wheeler Waring. [online] Available at: https://www.artnet.com/artists/laura-wheeler-waring/.

- Wikipedia Contributors (2025). Suzanna Ogunjami. Wikipedia.

- Ottenberg, S. (2015). Conflicting Interpretations in the Biography of a Modern Artist of African Descent. Journal of West African History, [online] 1(2), pp.45–69. Available at: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/640360/summary [Accessed Nov. 2025].

- Phillipscollection.org. (2024). The Women of African Modernism. [online] Available at: https://www.phillipscollection.org/blog/2024-01-06-women-african-modernism.

- Wikipedia Contributors (2019). Disfranchisement. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disfranchisement.

- Wikipedia Contributors (2019). Intersectionality. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intersectionality.

- Wikipedia Contributors (2018). Jim Crow laws. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Crow_laws.

- Singh, S. (2025). Why We Want to Be Remembered: The Quiet Human Hunger for Legacy. [online] Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@saumya.singh1817/why-we-want-to-be-remembered-the-psychology-behind-legacy-and-human-connection-752f971c3b05 [Accessed. 2025].

- Jenainati, C., Groves, J. and Milton, J. (2019). Feminism: a graphic guide. London: Icon Books Ltd.

- Lorde, A. (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. S.L.: Penguin Books, p.114.

REFERENCES FOR IMAGES [IN ORDER]

- The judgement day by Aaron Douglas https://www.nga.gov/artworks/166490-judgment-day

- Arreau, Hautes - Pyrenees by Louis Mailou jones https://nmwa.org/art/artists/lois-mailou-jones/

- Ode to Kinshasa by Louis Mailou jones https://nmwa.org/art/artists/lois-mailou-jones/

- Portrait of a boy https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Portrait-of-a Boy/4F7E43CB911C24FFB22A75C0107EB63E

- After Sunday Services by Laura Wheeler Waring https://mydailyartdisplay.uk/2023/12/04/laura-wheeler-waring-part-1/

- Full blown magnolia by Suzanna Ogunjami https://longlistshort.com/tag/suzanna-ogunjami/

- A Nupe Princess by Suzanna Ogunjami https://www.phillipscollection.org/blog/2024-01-06-women-african-modernism

- Audre Lorde https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/mighty-voice-black-feminist-intellectual-audre-lorde-s-essay-book-n822626