Emory Douglas - underrepresentation within design

Wikipedia-Style Entry

Introduction

I acknowledge that there is already a Wikipedia page for Emory Douglas, however, I have decided to expand upon this.

Emory Douglas (born May 24, 1943) is an American graphic artist, political designer, and influential cultural figure, best known as the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party (BPP) College of Marin Library (2023). This entry goes beyond the usual public account of Douglas’s life, giving a closer look at his artistic approach, political impact, and importance in global protest culture and Black visual history. Douglas helped shape the look of the Black Panther movement, turning political graphics into powerful tools for empowerment, education, and resistance.

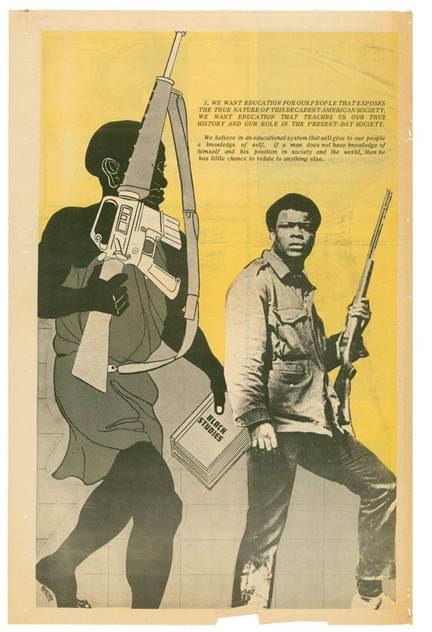

Figure 1: Emory Douglas artwork reproduced in Letterform Archive collections (Letterform Archive, 2017).

Early Life and Education

Douglas was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and raised in San Francisco after his family relocated to California. His first exposure to graphic design came at a youth correctional facility in Ontario, California (which lasted 15 months), where he worked in the print shop and learned typesetting, layout, and mechanical reproduction skills. These experiences were fundamental to his later artistic practice. Following his release, Douglas studied commercial art at City College of San Francisco, where he encountered the emerging radical political climate of the mid-1960s Bay Area, which would heavily influence his own views. Modica, A. (2009)

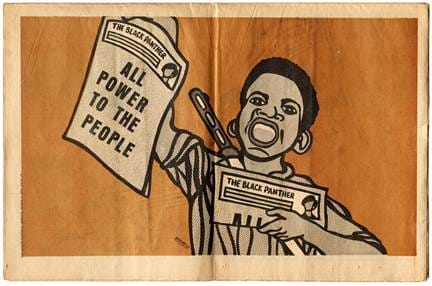

Figure 2: Early Black Panther layouts featuring Douglas’s design style (Letterform Archive, 2017).

Joining the Black Panther Party

In 1967, Douglas was recruited into the Black Panther Party by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale at the Black House (a political centre in San Francisco). His artistic skills earned him the role of Minister of Culture, which placed him in charge of the party’s official newspaper, The Black Panther. Douglas developed a distinctive visual language using bold lines, high contrast, and powerful symbolism, forming a system to communicate the Party’s messages to communities often excluded from mainstream media. Miranda, C.A. (2015)

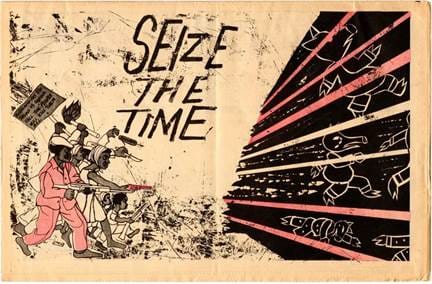

Figure 3: Emory Douglas illustration reproduced in Black Ink (Black Ink, 2018).

Themes and Style

Douglas’s aesthetic blended realism with graphic elements. His designs were highly stylized yet expressive, often depicting Black people in empowered, dignified roles such as workers, mothers, elders, and self-defenders. This challenged negative media portrayals and helped foster a sense of political agency. He also employed recurring symbolic motifs, such as pigs to represent police and imperialists, as well as the black power salute which is an important symbol within the black power movement. His work aimed to democratize political art, making it accessible to audiences regardless of literacy level or artistic training. (Tate, Rhodes, J. (2007))

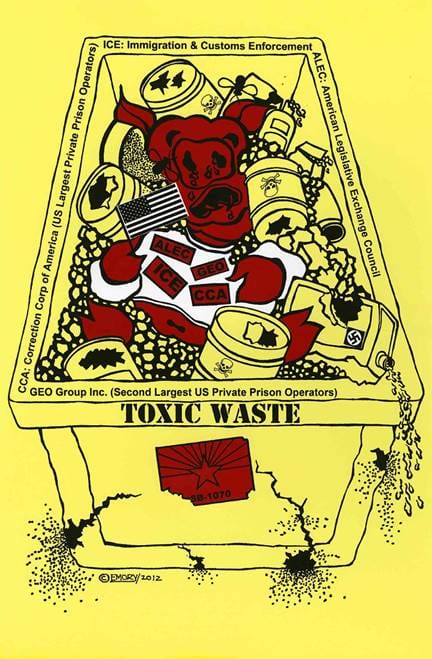

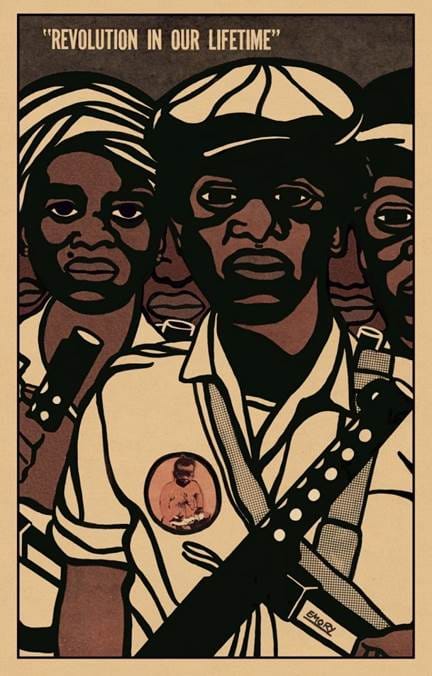

Figure 4: Black Panther social program poster reproduced in College of Marin Library exhibition (College of Marin Library, 2023).

Impact and Global Influence

Douglas’s graphics circulated internationally through posters, newspapers, and solidarity campaigns. His work influenced anti-colonial movements in Africa, the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia. The aesthetics of Black Power developed largely through Douglas’s visual strategies, which helped unify local struggles into a shared global vision of resistance.

Figure 5: Anti‑imperialist artwork reproduced in Rollins Museum of Art resources (Rollins Museum of Art, 2020).

Institutional Reception and Recognition

For decades, Douglas remained overlooked by mainstream institutions due to the Panthers’ radical politics. Museums and textbooks tended to avoid artists associated with militant or anti-state views, instead emphasizing politically safer figures. Only in the 2000s did major art institutions start recognizing Douglas’s importance through different Projects and exhibitions.

Figure 6: Emory Douglas poster reproduced in College of Marin Library exhibition (College of Marin Library, 2023).

Later Work and Legacy

In later decades, Douglas continued creating artwork that addressed mass incarceration, environmental injustice, and global inequalities. He collaborated with activist art groups and gave extensive lectures. Today, he is recognised as one of the most influential political designers of the twentieth century, a foundational figure in Black visual culture, and a pioneer of socially engaged graphic design worldwide.

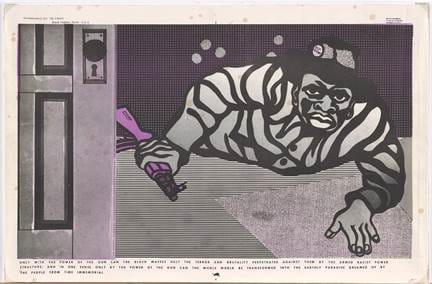

Figure 7: Anti‑police brutality illustration reproduced by Rollins Museum of Art (Rollins Museum of Art, 2020).

Analytical Argument (600 Words)

Introduction

Emory Douglas’s marginalization within mainstream art and design history illustrates how institutions selectively shape cultural memory throughout history. Although Douglas played a central role in shaping the Black Panther Party's visual identity, “visually articulated the politics of the party with fearless images that were unambiguous in content and style.” Gaiter, C. (2007), His work remains significantly underrepresented. This absence reflects broader cultural unease with radical Black politics and shows how institutional narratives suppress forms of protest that challenge dominant power structures within America, still to this day.

Institutional Discomfort with Radical Black Politics in America

Mainstream art institutions often accept political artists whose messages match liberal humanitarian ideals while avoiding works connected to radical resistance. Douglas’s graphics targeted police violence, capitalism, and white supremacy in straightforward and uncompromising ways. Because these themes remain politically sensitive, museums and galleries have historically avoided displaying Douglas’s work alongside figures like Shepard Fairey or Keith Haring, whose activism is less confrontational to the state.

Sanitised Civil Rights Narratives

Douglas’s erasure is further supported by the sanitized portrayal of Civil Rights history. Mainstream stories focus on peaceful protests and individual leaders, often downplaying the role of revolutionary groups such as the Black Panther Party which is explored within (black against the empire (2013), Douglas’s artwork served as a form of political education for several marginalized communities, showcasing ideals of autonomy, self-defense, and community resilience. Recognizing his contributions involves bringing forth the larger movement which helps to validate the importance of revolutionary activism.

Black Visual Culture and Community-Based Design

Douglas’s work was central to the development of Black Power aesthetics. His imagery circulated widely outside formal art spaces, redefining the relationship between design and everyday life, “They managed to rewrite the users manuals of not only ‘visual communication’ but also of art dissemination.” Black Ink (2018). While Black fine artists of the era are now celebrated in exhibitions like ‘Soul of a Nation,’ Douglas, whose graphics reached millions, remains less widely taught. His work democratized aesthetics by grounding political art in community realities which didn’t blend well with Americas political artistic systems.

Structural Exclusions in Design History

The marginalisation of Douglas reflects broader systemic issues within design history. Black designers engaged in activism or community organizing are often excluded from canonical texts. Publications such as (Here: Where the Black Designers Are, 2024; The Black Experience in Design: Identity, Expression & Reflection, 2022) document how these exclusions persist. Douglas’s practice demonstrates that design can function as a form of political literacy and empowerment rather than simply a commercial tool.

Conclusion

Restoring Douglas to the centre of art and design history requires rethinking the frameworks that determine which artworks are preserved and celebrated . His work exemplifies design as a tool of liberation and community strength “Douglas’s stylized illustrations of dark-skinned, full-lipped, broad-nosed African-featured people visualized blackness in a way that was virtually absent from mainstream media in the 1960s.” Rollins Museum of Art (2020). Recognizing Douglas expands the boundaries of design history and corrects an important refinement which is still needed in the cultural record.

References

Black Ink (2018) An Interview with Emory Douglas [online]. Black Ink website. Available at: https://black-ink.info/2018/10/03/an-interview-with-emory-douglas/

Bloom, J. and Martin, W. E. (2013) Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

College of Marin Library (2023) The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas [online]. College of Marin Library blog. Available at: https://library.marin.edu/blog/revolutionary-art-emory-douglas

Douglas, E. and Berger, M. (2007) Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas. New York: Rizzoli.

Letterform Archive (2017) Emory Douglas & The Black Panther [online]. Letterform Archive website. Available at: https://letterformarchive.org/news/emory-douglas-and-the-black-panther

Miranda, C.A. (2015) ‘Meet Emory Douglas, the revolutionary artist of the Black Panthers’, Los Angeles Times, 21 February. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/

Modica, A. (2009) ‘Emory Douglas (1943– )’, BlackPast.org, 14 November. Available at: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/douglas-emory-1943/

Rhodes, J. (2007) Framing the Black Panthers: The Spectacular Rise of a Black Power Icon. New York: The New Press.

Rollins Museum of Art (2020) Revolutionary Newspaper Art [online]. Rollins Museum of Art blog. Available at: https://blogs.rollins.edu/rma/2020/06/23/emory-douglass-revolutionary-newspaper-art

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art ‘Emory Douglas’, SFMOMA Artist Bio. Available at: https://www.sfmoma.org/artist/emory-douglas

Tate Modern (2017) Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power [online]. Tate Modern website. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/soul-nation-art-age-black-power

Tate Modern (n.d.) ‘Emory Douglas’, Tate Artist Biography. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/emory-douglas

Tate Modern (n.d.) ‘Emory Douglas’, Tate Artist Biography. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/emory-douglas