Cheryl Miller wikipedia 5.3 Entry

Cheryl D. Miller is an American Graphic designer, educator, author and advocate, known for her work promoting equity and inclusion for Black graphic designers. She founded one of the first Black woman–owned design firms in New York City in 1984, under the name Cheryl D. Miller Design, Inc.

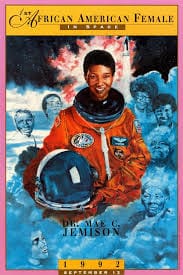

During the years her studio operated, roughly 1984 through 2000, Miller’s firm completed commissioned commercial work for major clients. These included corporate identities, publications, brochures and posters for institutions and companies among them are: BET, American Express, Chase Bank, Time, Inc., and NASA. Notably, in 1992 she was commissioned by NASA to design a poster for Mae C. Jemison, the first Black woman astronaut. This commercial work demonstrates that Miller was actively engaged in professional design practice, producing work for clients rather than exclusively creating personal artwork.

Alongside this commissioned work, Miller developed her own projects centred on advocacy, writing and the documentation of Black designers’ history. In 1987 she authored a landmark article titled Black Designers: Missing in Action for PRINT Magazine. That article grew out of her graduate thesis at Pratt Institute, and exposed the lack of representation, opportunity, and visibility for Black designers in the industry. In Later years she continued to write about these issues. She created a follow-up article in 2016 and a four-part series in 2020 under the title Black Designers: Forward in Action which renewed her call for inclusion and structural change in design.

Her contributions include more than just writing. Miller has donated a large collection of her professional work and historical research to academic institutions for preservation. For example, in 2022 she gifted material to the Herb Lubalin Study Center of Design and Typography at The Cooper Union, establishing a dedicated collection focused on Black graphic design history. The collection includes over fifty pieces including her graduate thesis, original posters (including the Mae Jemison poster), and a variety of corporate and social-justice design works. Through this archival work, Miller helps preserve a record of Black designers’ contributions for future generations.

Miller has also engaged in teaching, lectures and public events to further her advocacy. She is a Distinguished Senior Lecturer in Design at University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin), and she holds academic appointments at institutions such as Howard University. Her academic credentials include a BFA in Graphic Design from the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), an MS in Communications Design from Pratt Institute, and foundation studies at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).

Her combined work, professional design, scholarship, archival donations and teaching situates her as both a working designer and a campaigner. Her 1987 article challenged the design industry to confront racism and exclusion. Decades later she deepened that challenge with new writing and by building institutions (collections, archives, databases) to document Black designers.

In recognition of these accomplishments, Miller has received major awards. In 2021 she was awarded the AIGA Medal for “Expanding Access.” In the same year she received the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award as a “Design Visionary,” along with the honorary title of “Eminent Luminary” by IBM. In 2022 she was inducted into the Creative Hall of Fame.

Cheryl D. Miller deserves much more attention in the design world. She is not only a skilled designer but also someone who shows how unfair the system can be for Black designers. Her career is full of achievements, yet she is still not spoken about as much as she should be. When we look at the quality of her work and the effort she puts into helping others, it becomes clear that her voice should be heard more often.

One main reason she should be more represented is the success she had as a designer. She ran her own Black owned design studio and worked with major clients that usually hired only the biggest firms. This proves that Black designers are fully capable of doing work at the highest level. Her success challenges the idea that Black designers are less skilled or unable to compete. Instead, it shows that they can do just as well when given a fair chance. Her experience makes us question why many talented designers are overlooked, and that is one of the strongest arguments for giving her more recognition.

Another reason she deserves more attention is her willingness to speak out against unfair treatment. Instead of keeping quiet and focusing only on her own career, she chose to write about the problems Black designers face. She pointed out that many Black designers never get noticed even though they are qualified and creative. She asked why the design industry ignores so many talented people. She also explained that this harms design as a whole because it loses new ideas and different perspectives. Her message encourages the design community to reflect on these issues and improve.

Miller also challenges what people are taught about design history. Many students grow up thinking that there is only one correct way to design. However, Miller argues that this idea comes from only one cultural viewpoint. She believes that design should include different styles and influences. When students see only one version of history, they might think their own ideas do not matter. Miller’s work helps make design education more open and welcoming to many backgrounds. This is an important part of why her ideas should be shared more widely.

She also deserves more representation because of her work in preserving the history of Black designers. Instead of ignoring this missing history, she collected designs, documents and examples of work so they would not be forgotten. She made sure future designers could learn about these important contributions. This work protects knowledge that might otherwise disappear. If the design industry fails to show this history, it sends the wrong message that only certain people matter. By giving attention to Miller’s efforts, we create a more complete and honest design history.

All of these points lead to the same conclusion. Cheryl D. Miller should be treated as a central figure in design, not as someone who is added on at the edges. Recognising her is not just about celebrating one designer, but about supporting a fairer and more diverse design field. She represents the idea that everyone should have a voice and that design should include many viewpoints, not just one.

If people continue to overlook her work, students will learn only part of design history and the same mistakes will be repeated. However, if her ideas are shared and taught, design can become more open, creative and representative of society. Her work deserves to be discussed and valued, not pushed aside. She shows that real change is possible and that design can grow stronger when more voices are included.

Cooper Union. Cooper Union establishes collection of Black design with Cheryl D. Miller’s gift. Available at: https://cooper.edu/art/news/cheryl-d-miller-gifts-collection-work-black-designers-lubalin

Creative Hall of Fame. Cheryl D. Miller biography. Available at: https://creativehalloffame.org/inductees/cheryl-d-miller/

Print Magazine. (1987) Black designers: missing in action. Available at: https://www.printmag.com/design-culture/black-designers-missing-in-action-1987/

Print Magazine. From “Black designers: missing in action” to “Forward in action”: 3 essential industry articles. Available at: https://www.printmag.com/design-inspiration/from-black-designers-missing-in-action-to-forward-in-action-3-essential-industry-articles/

University of Texas at Austin. Cheryl D. Miller: faculty profile. Available at: https://designcreativetech.utexas.edu/cheryl-d-miller

Wikipedia. Cheryl D. Miller. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheryl_D._Miller