Abi Campling 5.3 Eilish Briscoe beyondthecanon

Part 1- Eilish Briscoe

Eilish Briscoe is an artist and graphic designer from Lancashire, now living and working in London (Briscoe, 2023). Her creative practice focuses on health, lived experience and communication, examining how the body, disability and language shape expression. In 2020, at the age of 25, Briscoe had a basilar thrombotic stroke, which left her temporarily unable to speak or write (It’s Nice That, 2024). This became a defining moment in her life and career direction; it changed her relationship with creativity and gave her practice a personal spark.

Education

Before entering graphic design, Briscoe studied Fine Art at university, graduating without doing anything relevant to her degree (Campling, 2025). Briscoe did not initially take a career in a conventional fine art environment. Instead, her work evolved through personal exploration. After her stroke, she began to connect her skills, lived and navigated through experience and began her real creative practice (Campling, 2025). This demonstrates that Briscoe’s development into design was shaped by her circumstances, recovery, and reflection.

Life and Career

Briscoe describes her stroke as the spark for her career in communication-based design. She stated, “For me, it was like my whole world had been turned upside down… I thought I would never be able to pick up a pen or pencil again, let alone create something beautiful” (Reynolds, 2022). The long process of rehabilitation forced her to attempt to relearn how to move physically like writing, which made her recognise that communication is not only an ability but also “a luxury” (It’s Nice That, 2024). She discovered that expression involves both the body and the mind, and that vulnerability can hold an artistic value.

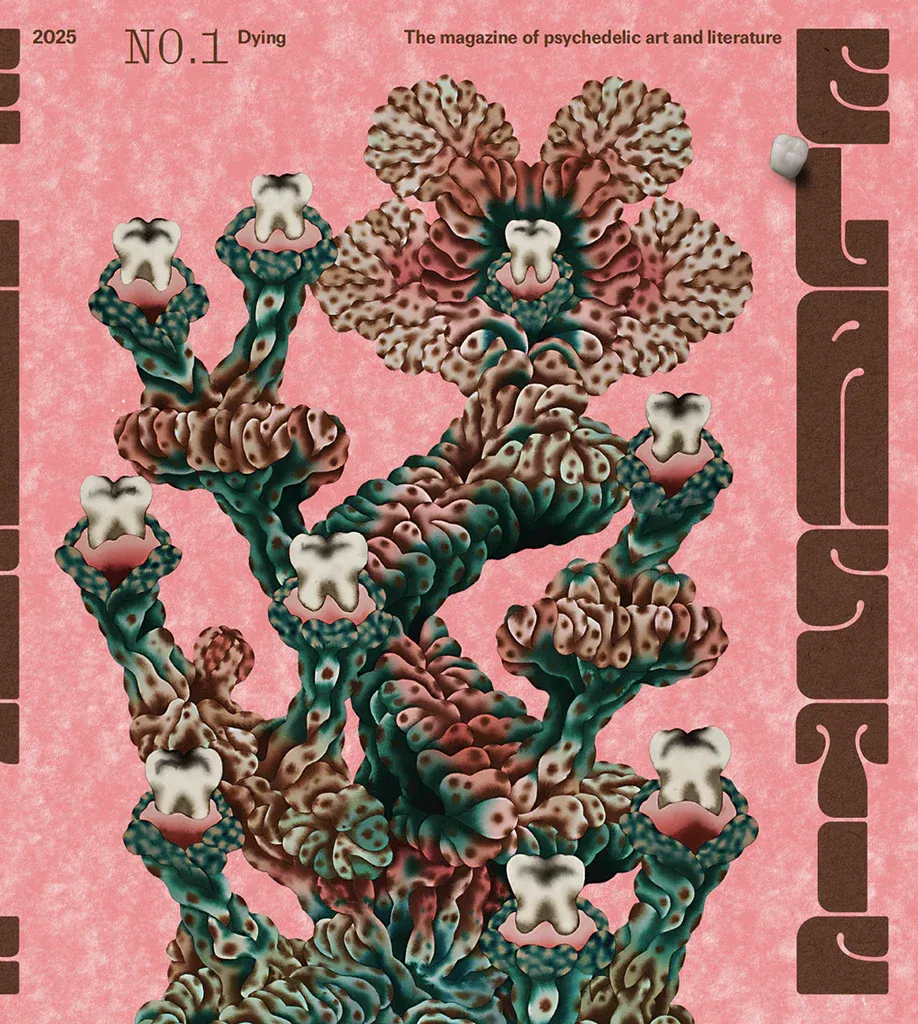

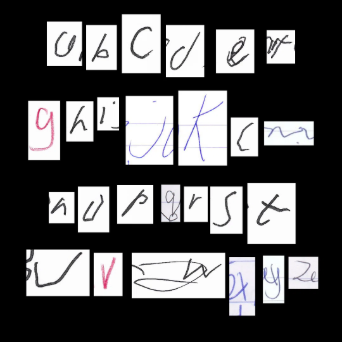

Briscoe created the typeface ‘Maybe’, as a visual journal of her relearning how to write after her stroke. Briscoe’s lettering was influenced by 'Dysfluent' Conor Foran, who created typographic work around speech impediments (Campling, 2025). Rather than trying to hide or “fix” her tremor, she tried to embrace it. She explained, “Every letter I made was uncertain — so Maybe felt like the right name” (May, 2025). The typeface is designed to reject perfection and instead frames uncertainty as honesty. It communicates that language and design do not need to be perfect to be meaningful. 'Maybe' is therefore both a type specimen and documentation of her survival.

Exhibitions and Achievements

Briscoe’s work has been showcased in different exhibitions exploring communication and disability. She made stencil-based work that was featured in two exhibitions: Make Your Own Masters: Open Cells in London and Expression is a Luxury at K-House, Manchester (Hingley, 2024). These exhibitions reflect her growing recognition within public design spaces. Her work has also extended into other collaborations, including exploring the relationship between aphasia, music, and visual communication (Campling, 2025).

Work Projects and Clients

Before her stroke, Briscoe worked in commercial creative production roles at Optical Arts, where she was credited on several major campaigns. She worked as a Production/Creative Assistant on the MADE.com “Never Ordinary” campaign (Optical Arts). She was also a Studio Assistant on the Dom Pérignon Plénitude II (Vintage, 2004) luxury campaign (ArtPractice) and contributed as a Studio Assistant to the post-rebrand Channel 4 Idents developed with 4creative and Art Practice (Optical Arts). These roles positioned her within high-level commercial design before she later shifted into her health/ experience-based art work.

In addition to these roles, Briscoe has worked on visual material for musical performances for a group called Aphasia and produced Spotify cover artwork for the singles Power of One and We All Gotta Eat (Campling, 2025). These projects highlight her reach across different types of work, showing her growth as a recovering designer.

Bibliography

ArtPractice. (n.d.) Dom Pérignon – Plénitude II (Vintage 2004). Available at: https://artpractice.studio/editions (Accessed: 3rd November 2025).

Briscoe, E. (2023) Portfolio Website. Available at: https://www.eilishbriscoe.com (Accessed: 1st November 2025).

Campling, A. (2025) Interview with Eilish Briscoe.

Hingley, L. (2024) ‘Expression is a Luxury Exhibition Review’, K-House Journal. Available at: https://www.manchestersfinest.com/events/expression-is-a-luxury-manchester-may-2024/ (Accessed: 2nd November 2025).

It’s Nice That. (2024) ‘Eilish Briscoe created a typeface to show the process of learning to write again’. Available at: https://www.itsnicethat.com/features/eilish-briscoe-maybe (Accessed: 1st November 2025).

May, L. (2025) ‘Typeface Review: Maybe’, The Design Journal, 21 March. (Accessed 5th November) (Link unavailable 1st December).

Optical Arts. (n.d.) Made — Never Ordinary. Available at: https://opticalarts.studio/work/projects/made-never-ordinary (Accessed: 5th November 2025).

Optical Arts. (n.d.) Channel 4 Idents. Available at: https://opticalarts.studio/work/projects/channel-4-idents (Accessed: 5th November 2025).

Reynolds, S. (2022) ‘What Happens When Language Breaks?’, Creative Review, 12 July. (Accessed: 1st November) (Unavailable 1st December).

Part 2 Argument

What’s the problem?

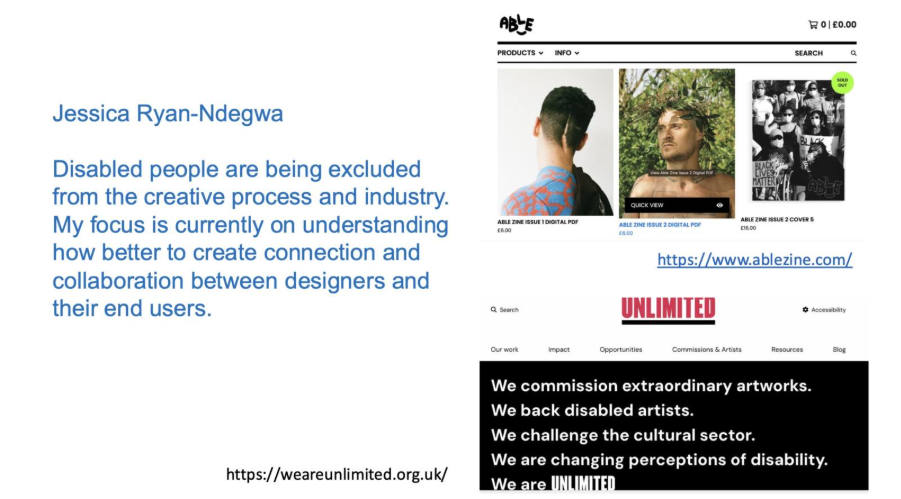

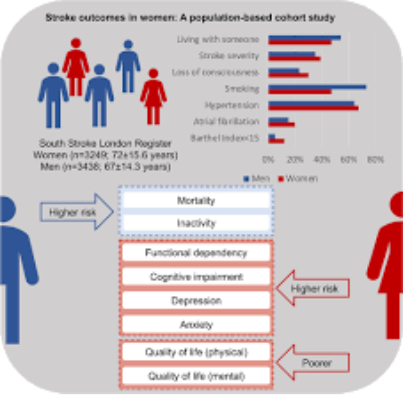

Disabled graphic designers continue to be significantly underrepresented in graphic design, and the experiences of Eilish Briscoe, who became disabled following a stroke at age 25, highlights the barriers that contribute to this. Stroke survivors frequently face long-term physical, cognitive and communicative challenges that directly impact their creative abilities, which the design industry often looks over and don’t accommodate these people. Briscoe’s journey shows how disability can reshape creative practice, while also exposing why disabled designers struggle to gain equal visibility and recognition. Strokes often produce complex neurological impairments that influence motor control, language and functioning abilities (Elliott & Flood, 2018). For many, including younger adults, the effects can be sudden, life-altering, and long-term. Briscoe’s thrombotic stroke in 2020 left her unable to speak or write (It’s Nice That, 2024), conditions commonly associated with brainstem strokes, which frequently impair fine-motor movements, coordination, and speech production (Keller & Tursky, 2020). Motor impairment can make essential design skills such as sketching, writing, cursor control, or even software interaction are significantly more difficult, if not temporarily impossible. Cognitive fatigue, reduced processing speed, and reduced attention span are all common post-stroke effects (Cumming et al., 2013), further complicate inclusion in an industry that prioritises things like speed and an uninterrupted flow of work.

These factors show why stroke survivors, even highly skilled creators, are often pushed out of traditional graphic design roles. The field’s pace and emphasis on precision can leave little room for designers whose creative processes involve physical fluctuation. Briscoe’s rehabilitation forced her to confront these barriers directly. This was the process of relearning to move that made her recognise communication as “a luxury” (It’s Nice That, 2024). This shows the structural mismatch between the realities of disabled designers and the expectations of the design sector.

‘Maybe’ Typeface

The creation of her typeface ‘Maybe’ demonstrates how disability can be transformed into a valuable creative method yet also exposes industry biases. Her tremor, rather than being hidden, became the basis of her typographic forms. As Briscoe explains, “Every letter I made was uncertain — so Maybe felt like the right name” (May, 2025). Her approach resonates with other disability-centred typographic work such as Conor Foran’s dysfluent design (Campling, 2025), aligning her work with a broader movement that challenges normative ideas of readability. However, the need to justify such work against able-bodied standards reveals how disabled designers must constantly prove their capabilities. The industry’s preference for polished work often excludes people whose physical impairments disrupt such expectations.

Underrepresentation is also demonstrated by the effects a stroke can introduce into educational and career pathways. Strokes in young adults frequently can disrupt training, employment and skill development (Ekker et al., 2018), which can derail entry into design careers. Briscoe graduated from a Fine Art course without pursuing a specific creative route until after her stroke (Campling, 2025), showing how life-altering health setbacks disrupt traditional creative development. Designers with disabilities often enter the sector later or through non-traditional routes, limiting their visibility in the early-career networks that shape who becomes recognised.

Although Briscoe had experience in high-end commercial studios such as Optical Arts and contributed to campaigns for MADE.com and Channel 4 (Optical Arts), her public recognition increased only after her stroke and disability-centred work. This illustrates a further barrier that disabled designers are often “contained” within disability-themed exhibitions, such as Expression is a Luxury (Hingley, 2024), rather than mainstream design. Their inclusion remains conditional and framed by narratives of recovery rather than professional recognition.

Over all, disabled graphic designers are underrepresented because design culture is built around assumptions of able-bodied speed, precision, and uninterrupted productivity. Briscoe’s path demonstrates both the barriers created by these norms and the creative insight that emerges when they are challenged. Until the design industry fully values diverse modes of communication and expression, disabled designers will continue to be marginalised.

Bibliography

ArtPractice. (n.d.) Dom Pérignon – Plénitude II (Vintage 2004). (Accessed: 3 November 2025). Available at: https://artpractice.studio/editions

Briscoe, E. (2023) Portfolio Website. (Accessed: 1 November 2025). Available at: https://www.eilishbriscoe.com

Campling, A. (2025) Interview with Eilish Briscoe.

Cumming, T., Marshall, R. & Lazar, R. (2013) ‘Stroke, cognitive deficits and rehabilitation’, Neuropsychology Review, 23(1), pp. 1–9. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23280268/

Elliott, M. & Flood, V. (2018) Neurological Rehabilitation: A Patient-Centred Approach. London: Routledge. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23280268/

Ekker, M., Boot, E., Singhal, A. et al. (2018) ‘Stroke in young adults: epidemiology and long-term outcomes’, Nature Reviews Neurology, 14(6), pp. 325–335. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30129475/

Hingley, L. (2024) ‘Expression is a Luxury Exhibition Review’, K-House Journal. Available at: https://www.manchestersfinest.com/events/expression-is-a-luxury-manchester-may-2024/ (Accessed: 2nd November 2025)

It’s Nice That. (2024) ‘Eilish Briscoe created a typeface to show the process of learning to write again’. (Accessed: 1 November 2025). Available: https://www.itsnicethat.com/features/eilish-briscoe-maybe

Keller, S. & Tursky, P. (2020) ‘Brainstem Stroke and Motor Impairment’, Journal of Clinical Neurology, 16(4), pp. 512–520. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560896/

May, L. (2025) ‘Typeface Review: Maybe’, The Design Journal, 21 March. (Accessed 5th November) (Link unavailable 1st December).

Optical Arts. (n.d.) Made — Never Ordinary. (Accessed: 5 November 2025). Available at: https://opticalarts.studio/work/projects/made-never-ordinary

Optical Arts. (n.d.) Channel 4 Idents. (Accessed: 5 November 2025). Available at: https://opticalarts.studio/work/projects/channel-4-idents

Reynolds, S. (2022) ‘What Happens When Language Breaks?’, Creative Review, 12 July. (Accessed: 1st November) (Unavailable 1st December).

Photos

American Heart Association 23rd June Available at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ahajournals.org%2Fdoi%2F10.1161%2FSTROKEAHA.121.037829&psig=AOvVaw3kYlsPbUVmDYIsb9kwlH2h&ust=1764668186072000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBYQjRxqFwoTCPis0byLnJEDFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE (Accessed 1st December)

Eilish Briscoe (n.d) Available at: https://www.instagram.com/eilishbriscoe/ (Accessed 1st December).

Home Of Unlimited (n.d) (Accessed 1st December) Available at: https://weareunlimited.org.uk/

Hingley, O., 2024. After having a stroke at 25, Eilish Briscoe created a typeface to show the process of learning to write again. It’s Nice That, 19 September. Available at: https://www.itsnicethat.com/features/eilish-briscoe-maybe-graphic-design-art-spotlight-190924 (Accessed 1 December 2025).

ManyPixels. 2024. Graphic Design Price, Speed & Quality: Can You Have it All?. ManyPixels. Available at: https://www.manypixels.co/blog/graphic-design/price-speed-quality (Accessed 1 December 2025).