5.3

Controversies in the Dune:

Adaptation-specific controversies

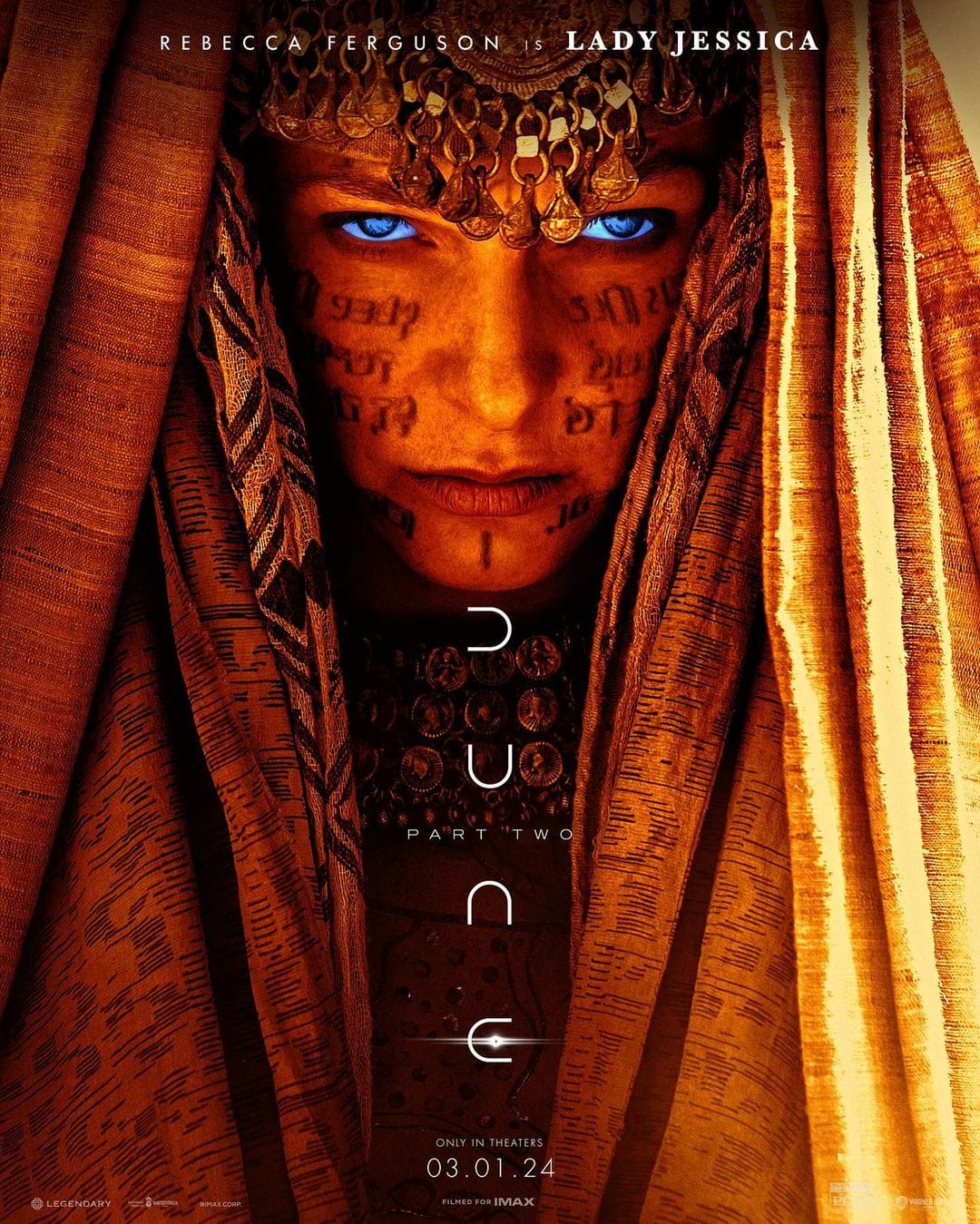

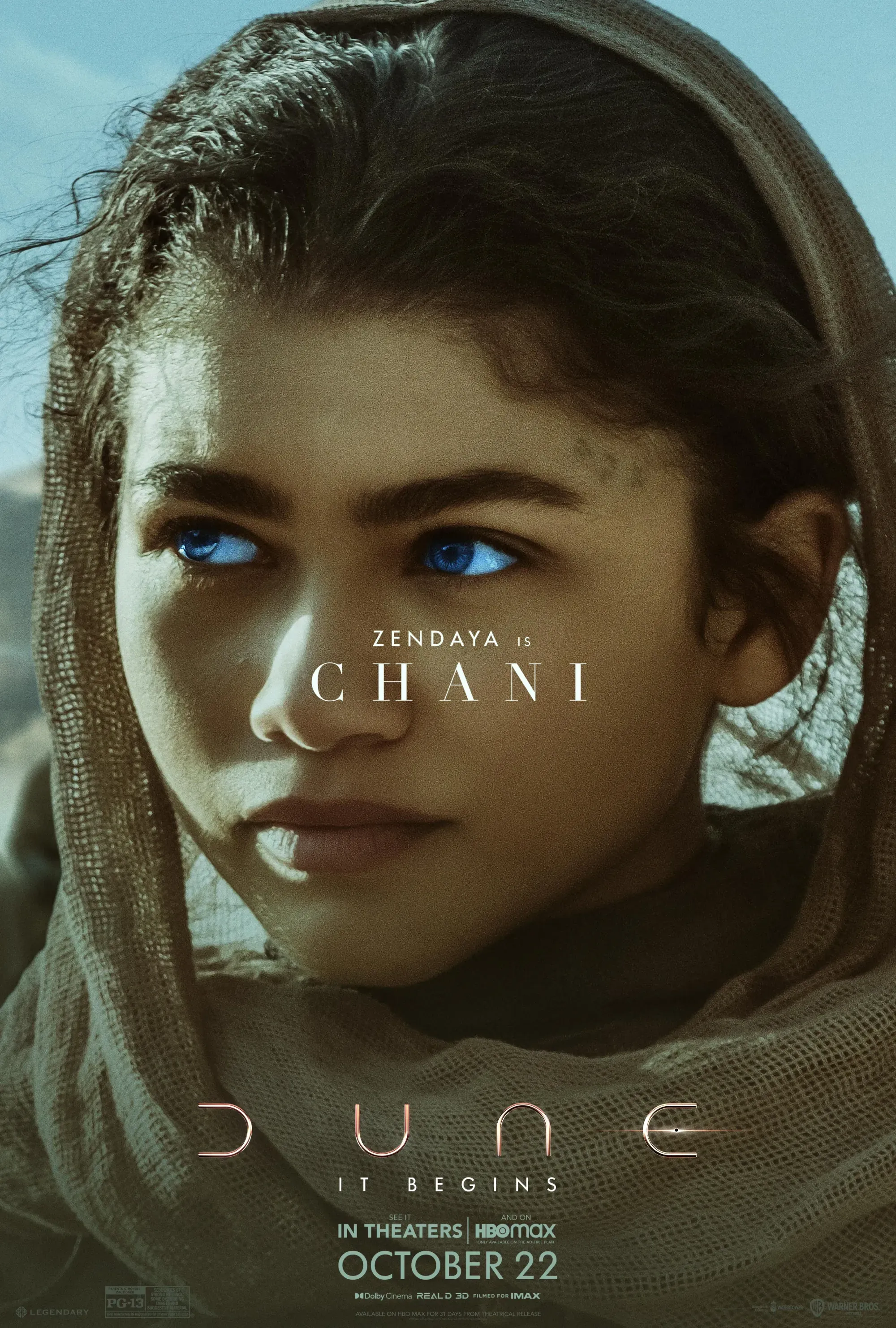

The film has received a lot of backlash from viewers due to several controversies that arose because of the film’s casting and its heavy relation to Islamic culture, while it draws heavily on Middle Eastern, North African (MENA), and Islamic culture. All of its major roles went to non-MENA actors, despite a significant portion of it being filmed in Jordan and the United Arab Emirates. This brought about criticism regarding cultural representation and authenticity. [6]

In addition, the term jihad used in the book was changed into the less politically charged “holy war” and “crusade” in the film, a choice seen as avoiding direct terminology to cater more to a Western audience. This change is also seen by some as cleansing the original story's complexity and the Fremen's religious/cultural inspirations.

Furthermore, the costumes in Dune have been criticised for orientalism due to their strong visual influences from Islamic and Middle Eastern traditional clothing. [3] [4]

Lack of consultation:

According to reports, the production did not involve cultural consultants from MENA or Muslim backgrounds. Jon Spaihts, a screenwriter for Dune: Part One, commented in an interview that the Arab world was considered “much more exotic in the 1960s” when the book was written, implying a deliberate distancing from modern-day associations. [9]

Cultural and political controversies:

The Dune franchise has long faced accusations of orientalist themes, with many people dubbing it as culturally insensitive. And with the release of the second movie, these discussions have been refuelled. Audiences and commentators have noted the similarities between the fictional Fremen and the real Middle Eastern and North African communities; parallels were highlighted when it came to appearance, cultural practices and desert environments. Some also interpret the film's resource ‘spice’ as a metaphor for petroleum, as the Middle East's main export. [2] [8]

Within the film, the Fremen are portrayed as nomadic desert dwellers with cultural and linguistic elements heavily inspired by MENA cultures; Arabic phrases were spoken throughout the film. However, some viewers argue that this reflects a broader pattern within Hollywood where it uses cultural aesthetics whilst the people associated with those cultures remain underrepresented on the screen. [1]

Critics claim that the portrayal of the Fremen reinforces the exotic tropes by painting them as mysterious and contributes to a “white saviour” narrative centred on Paul Atreides, the main character. Others, however, say that Dune goes beyond mere exoticism by exploring the source of the Fremen's strength and their capacity in the environment by incorporating critiques of imperialism within the original writing. [8]

Commentators have also shown concern that the film’s cultural inspirations are not only presented as exotic but also lack a deeper effort to show its deeply complex culture or engage with it in an accurate and respectful manner. [5] “While Dune: Part Two is an incredible film, it simply relegates its cultural inspirations to Orientalist aesthetics, which is frustrating at a time when such communities are openly discriminated against and demonised.” Furvah Shah, a critic, states [4]

The Arab and Muslim response to the film

The film received mixed reactions, with many appreciating the deep Islamic and Middle Eastern influences, while some others feel as though the films erase Arab culture and misrepresents them through a "white saviour" [8] narrative and the lack of MENA representation in key roles. [7]

Additionally, some viewers feel the portrayal of the Fremen and their religion and beliefs, even with its heavy Islamic influence, is a surface-level and or an inaccurate representation of MENA and Islamic culture. Some see its use of terms like "Mahdi" and themes of a messianic saviour as enriching, while others find it blasphemous and appropriative. [10]

References:

Dridi, Y. (2022) De-orientalizing Dune: Storyworld-Building Between Frank Herbert’s Novel and Denis Villeneuve’s Film. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366653898_De-orientalizing_Dune_Storyworld-Building_Between_Frank_Herbert's_Novel_and_Denis_Villeneuve's_Film [Accessed 18/11/2025]. [9]

Hosseini, M.A. (2021) The Orientalism of Dune. 3QuarksDaily. Available at: https://3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2021/10/the-orientalism-of-dune.html [Accessed 23/11/2025]. [3]

House & Garden (Davies, R.) (2022) Where was Dune: Part 2 filmed? Available at: https://www.houseandgarden.co.uk/article/dune-part-2-filming-locations [Accessed 21/11/2025]. [6]

Inkstick Media (Khelil, K.) (2021) Erasing Arabs from “Dune”. Available at: https://inkstickmedia.com/erasing-arabs-from-dune [Accessed 23/11/2025]. [7]

Irani, S. (2022) ‘Dune’ isn’t worthy of your praise. The Michigan Daily. Available at: https://www.michigandaily.com/arts/b-side/dune-isnt-worthy-of-your-praise [Accessed 21/11/2025]. [5]

Lapointe, G. (2022) Dune’s Intellectual Ableism as a Function of Its White Supremacy. Medium. Available at: https://gracelapointe.medium.com/dunes-intellectual-ableism-as-a-function-of-its-white-supremacy-9f910c54492b [Accessed 18/11/2025]. [8]

Mahabir, H. (2022) Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune’ and Orientalism. University of Kent. Available at: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/munitions-of-the-mind/2022/04/04/frank-herberts-dune-and-orientalism [Accessed 20/11/2025]. [1]

Poletti, J. (2024) Is ‘Dune’ a lot of white people in a Muslim story? Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/belover/is-dune-a-lot-of-white-people-in-a-muslim-story-3bce567e6c65 [Accessed 18/11/2025]. [2]

Shah, F. (2024) How Dune: Part Two erases its Middle Eastern, North African and Muslim influences. Cosmopolitan. Available at: https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/entertainment/a60007426/dune-2-middle-east-north-africa-muslim-influence-erasure [Accessed Day 11/2025]. [4]

Tectonic School & Sartori, M. (2024) Dune 2 – A Religious Critique. Available at: https://www.tectonicschool.com/p/dune-2-a-religious-critique [Accessed 30/11/2025]. [10]

My Argument

Orientalism in Dune:

Orientalism emerged in late 18th-century Europe; it stemmed from the growing interest by scholars in languages, literatures, histories, art, law and cultures of the East, especially during the colonial expansion era. The starting point for modern-day Orientalism is often attributed to France’s invasion of Egypt in 1798. Orientalism remains as relevant today as when Edward Said first introduced it. He argued that Orientalism was not solely the study of "the East" but a Western concept that was complicit in imperial power which had created a false contrast between the "superior West” and the "inferior, weak, or barbaric East” to serve colonial domination and control.

Dune’s involvement with Orientalism is a huge subject of debate among viewers and critics. Its author, Frank Herbert, originally intended the novel to be a critique of colonisation, imperialism, and the “white saviour” trope. Many argue that it utterly fails to do so, some going even further by saying that it manages to achieve the opposite, by relying on stereotypes, as well as using a colonialist perspective throughout the story.

Although some view the movie as an actual critique, others argue that it completely diverges from that by depicting the Fremen as uncivilised and rogue. The film depicts them as “noble savages” who are strong and spiritually intertwined with their land. This depiction goes further by framing them as primitive and extremists by the “Western” characters. This portrayal reduces them to a one-dimensional and stereotypical people, further reinforcing the “othered” narrative.

When viewing Dune through Edward Said's lens of Orientalism, it raises an argument against its foundation on how the film falls into the West’s warped image of the East or the Orient as being exotic and uncivilised; sometimes even dangerous despite it being a "critique". The film is an example of the West’s view of the East, the story relies heavily on familiar dichotomies like “West vs. East” portraying the West as rational, civilised, and technologically advanced. The Orient, however, is viewed as the more exotic and a technologically backwards society.

Furthermore, the movie not only portrays the Fremen as exotic but also the planet Arrakis, while the intention might have been to create an otherworldly setting. The depiction of the desert planet draws on stereotypes associated with the Middle East, such as cultural mysticism. Even visual choices, such as constant close-ups of Chani that highlight her mysteriousness and contribute to an Orientalist portrayal of women as exotic. The use of the Arabic language and Arabic-sounding names for characters and locations to make them seem more "foreign" making the film fall into “Orientalist generalisations” once again.

Said famously observed “that In newsreels or news-photos the Arab is always shown in large numbers. No individuality, no personal characteristics or experiences. Most of the pictures represent mass rage and misery, or irrational… Lurking behind all of these images is the menace of jihad. Consequence: a fear that the Muslims (or Arabs) will take over the world.” (page 287)

Dune uses many of the same Orientalist patterns that depict MENA people as culturally homogenous with no deeper complexity to its characters other than their superficial cultural influences. This narrative choice accompanied with lack of the colonised Fremens perspective ultimately limits the ability to fully critique the story from an indigenous point of view. The film imitates Islamic and MENA culture only to aestheticise their beliefs and history; Implementing a dehumanising narrative that oppresses individual experiences and cultures.

Whether intentional or not, the film and its source material continues to participate in the West’s longstanding practice of imagining the East through lenses of exoticism, primitivism, which are precisely the dynamics that are most harmful to (MENA) communities.

References:

Artan, A. (2024) Why Dune: Part Two fails to address Dune's biggest issue: It’s not a critique of colonialism – it’s an example of it. Digital Spy. Available at: https://www.digitalspy.com/movies/a60021028/dune-2-colonialism-orientalism [Accessed Day 23/11/2025].

Ashkenazi, O. (2021) Why Herbert’s Dune Fails as a Subversion: Frank Herbert is not a guy I would go to for political commentary. Mythcreants. Available at: https://mythcreants.com/blog/why-herberts-dune-fails-as-a-subversion [Accessed 22/11/2025].

Fahd, C. & Oscar, S. (2024) Is Dune an example of a white saviour narrative – or a critique of it? The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/is-dune-an-example-of-a-white-saviour-narrative-or-a-critique-of-it-225656 [Accessed 23/11/2025].

Hamade, R. (2024?) ‘Dune’ Through the Lens of Edward Said: Examining Orientalism and its Impact. ArtsHelp. Available at: https://www.artshelp.com/dune-through-the-lens-of-edward-said-examining-orientalism-and-its-impact [Accessed 25/11/2025].

Kennedy, K. (2024) Editorial – Chani and the Empowered Woman Stereotype in ‘Dune: Part Two’: No Family, No Faith, Just Fight. DuneNewsNet. Available at: https://dunenewsnet.com/2024/03/chani-empowered-woman-stereotype-dune-part-two-movie [Accessed 21/11/2025].

Said, E.W. (1978) Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

Taylor, C. (2022) Reading Dune as a Woman. Humanities Moments. Available at: https://humanitiesmoments.org/moment/reading-dune-woman [Accessed 25/11/2025].

wllms, R. (2022) Orientalism & the White Male Savior Complex in Dune (2021). RTF Gender and Media Culture. Available at: https://rtfgenderandmediaculture.wordpress.com/2022/07/02/orientalism-the-white-male-savior-complex-in-dune-2021 [Accessed 22/11/2025].